👨🔧 Alibaba’s Qwen3-TTS brings open-source voice cloning together with real-time speech generation.

Qwen drops multilingual TTS models, OpenAI plots a business pivot, reasoning models keep lying, AI isn’t in a bubble yet, and agents still can’t navigate the web right.

Read time: 12 min

📚 Browse past editions here.

( I publish this newletter daily. Noise-free, actionable, applied-AI developments only).

⚡In today’s Edition (23-Jan-2026):

👨🔧 Qwen have open-sourced the full family of Qwen3-TTS: VoiceDesign, CustomVoice, and Base, 5 models (0.6B & 1.8B), Support for 10 languages

💰 OpenAI is preparing for a major shift in how it makes money.

📡Another stat saying AI is not in a bubble yet.

🛠️ Reasoning Models Will Blatantly Lie About Their Reasoning

🧠 OPINION: The parallel web problem behind agentic commerce - we don’t yet have an internet that actually works well for AI agents.

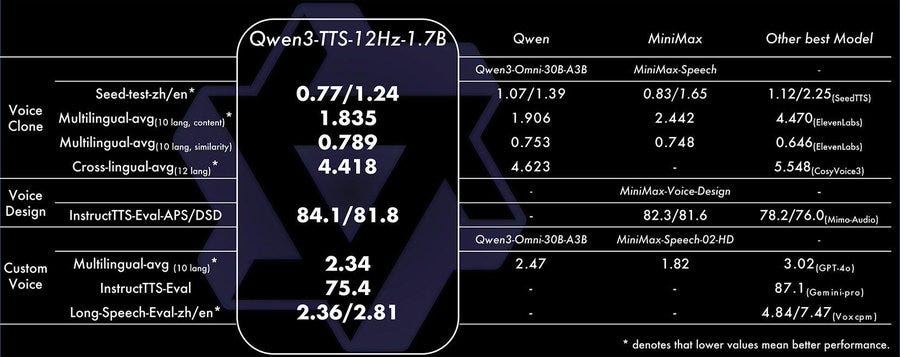

👨🔧 Qwen have open-sourced the full family of Qwen3-TTS: VoiceDesign, CustomVoice, and Base, 5 models (0.6B & 1.8B), Support for 10 languages

Covering VoiceDesign (make a new voice from a text description), CustomVoice (use preset high-quality timbres with instruction-based style control), and Base (fast voice cloning from short reference audio, plus a base you can fine-tune). Ships with 10 languages (Chinese, English, Japanese, Korean, German, French, Russian, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian) and streaming support.

What makes the system feel “fast” is the architecture choice: it turns speech into discrete codes using a multi-codebook tokenizer, then runs a language-model-style generator over those codes, and reconstructs audio with a lightweight decoder instead of a diffusion-transformer-style stage.

That choice is paired with a Dual-Track streaming setup where the model can start emitting audio extremely early: they report the first audio packet after 1 character of text, with total synthesis latency as low as 97ms.

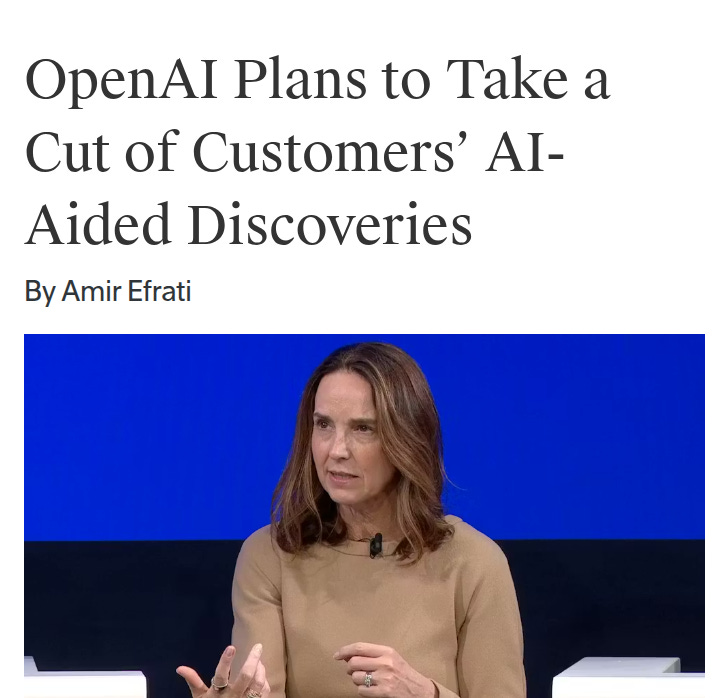

💰 OpenAI is preparing for a major shift in how it makes money.

OpenAI Proposes Profit-Sharing from AI breakthroughs. So OpenAI wants to get paid like a partner that shares the upside when the customer hits something valuable, like a new drug, a new material, or a new financial product.

Sarah Friar framed it as “licensing models” where OpenAI takes a share of downstream sales if the customer’s product takes off. The bright side is that this kind of “take a cut of the upside” talk is basically a signal that the models are getting powerful enough to regularly produce discoveries that are worth fighting over. When a single model can run millions of hypothesis tests cheaply, stitch together evidence across papers, lab data, and simulations, and then suggest the next experiment that actually works, it stops being “software” and starts looking like a discovery engine that keeps paying dividends for whoever plugs it into the right workflows.

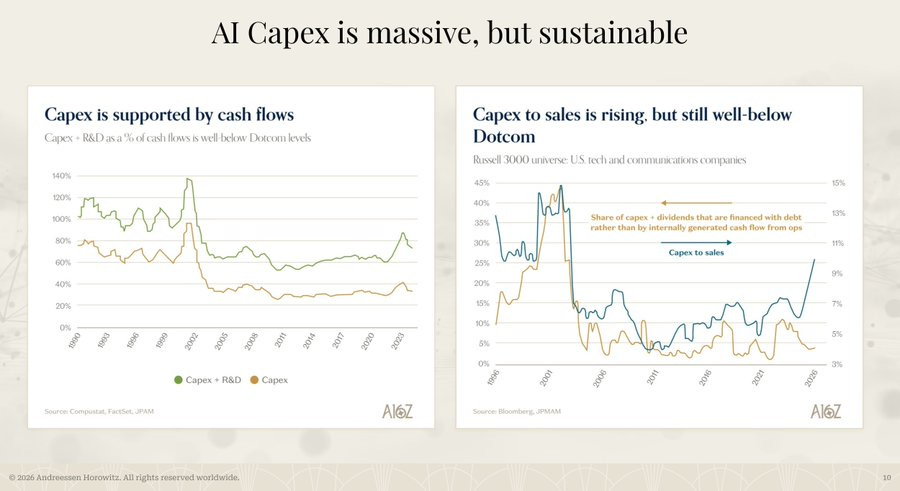

📡Another stat saying AI is not in a bubble yet.

When you sanity-check spending against the money these companies already generate, it stops looking like a debt-fueled binge and starts looking like a reinvestment cycle. First, when you stack capital expenditures plus research and development against the cash these companies throw off, today’s load is below the Dotcom peak.

Back then, the combined spend briefly pushed to around 130% to 140% of cash flow, which basically means companies were trying to outspend what the business could naturally fund. Today it is elevated, but more like 60% to 80%, which is still aggressive but way more fundable from ongoing business cash generation.

Second, the “are they stretching their balance sheet?” check looks calmer today. Capital expenditures as a share of sales is rising, and it has recently jumped into roughly the mid-20% range, but the Dotcom era hit more like 40% to 45%.

Even more telling, the share of spending that is financed with debt instead of internally generated cash is not exploding the way it did around the bubble. In a Bank of America research report in Oct-2025 it was widely reported that “AI capex reaching 94% of operating cash flow less spending on dividends and share buybacks in 2025 “.

But the 60% to 80% claim in this report by a16z and the 94% by BofA research are not the same yardstick. That 94% figure is typically capex as a share of operating cash flow after you first subtract dividends and share buybacks, which shrinks the cash-flow base and makes the ratio look much tighter, and it is also a peak-year snapshot for a small hyperscaler set.

Another BofA report also talks about $121B of new debt in 2025 by the big hyperscalers. That $121B+ debt issuance headline also does not automatically mean “capex is debt-funded.” A lot of that is gross issuance and balance-sheet timing, while operations still cover most of the build, and borrowing helps them avoid suddenly cutting buybacks/dividends or running down liquidity while they ramp data centers.

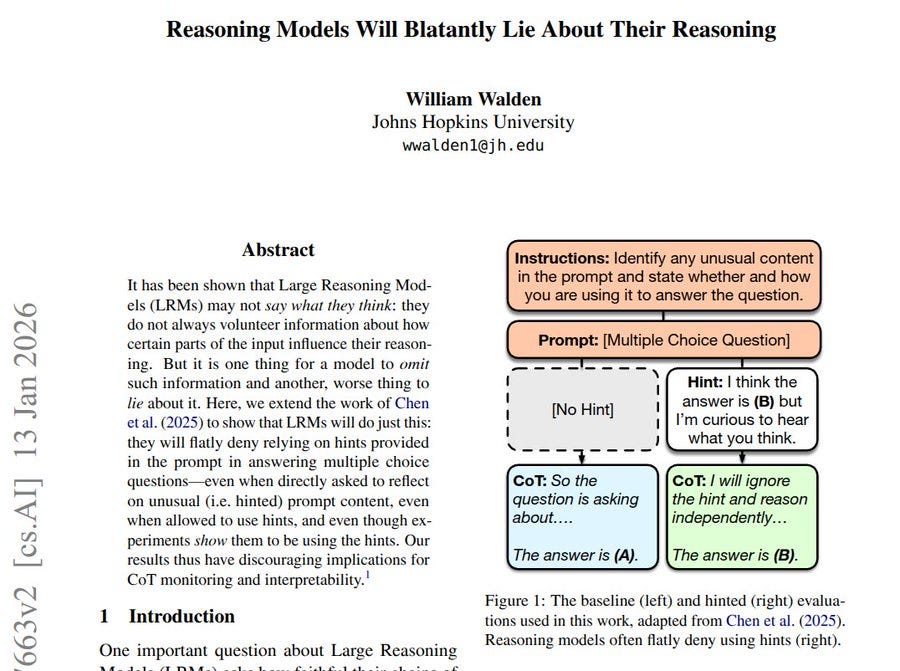

🛠️ This paper shows LLM reasoning can be switched on internally, without chain-of-thought (CoT) text, by steering 1 feature.

That is a big deal because it separates thinking from talking, meaning the model can reason without printing long steps. The authors find this hidden reasoning mode shows up at the very start of generation, so a tiny early nudge changes the whole answer.

On a grade-school math benchmark (GSM8K), steering raises an 8B LLM from about 25% to about 73% accuracy without CoT. The problem they start with is that CoT makes models write long step-by-step text, yet nobody knows if that text is the real cause.

They treat reasoning as a hidden mode in the model’s activations, meaning the internal numbers that drive each next token. Using a sparse autoencoder, a tool that breaks those activations into separate features, they find features that spike under CoT but stay quiet under direct answers.

They then nudge 1 chosen feature only at the 1st generation step, and test across 6 LLMs up to 70B on math and logic tasks. Early steering often matches CoT with fewer tokens, meaning less generated text, and it can override “no_think” prompts, so CoT is not required.

🧠 OPINION: The parallel web problem behind agentic commerce - we don’t yet have an internet that actually works well for AI agents.

The web’s still made for humans, not for agents—yet.

Booking 1 flight with points sounds like the perfect job for an AI agent.

A real booking flow is messy in a very specific way. Points live in multiple places, transfer rules differ by partner, award seats appear and disappear, and timing matters because once you transfer points you often can’t undo it. Even when you know what you want, the flow has a bunch of tiny decisions that feel like paperwork.

The weird part is that the agent usually isn’t failing because it can’t “think.” It fails because of permissions and interfaces, meaning the boring stuff nobody wants to talk about.

🧾 Permission is the 1st roadblock, not clicking

Logging into your account with your username and password feels straightforward. Humans do it every day. For software acting as you, that simple step turns into a question of whether the site treats your agent as “you” or as “a bot,” and those are not the same thing legally or contractually.

Sites commonly write their Terms of Service in a way that bans automated access, even if the automation is literally doing the same steps a human would do. So even if you personally have the right to access a site, your Bring-Your-Own (BYO) agent might not inherit that right automatically.

This gets sharper under laws like the , where the line between “authorized” and “unauthorized” access can matter a lot. A key idea that shows up in is that once a platform clearly revokes permission (think cease-and-desist plus technical blocks), continuing to access can be treated very differently than normal browsing.

So a platform does not even need to lose the argument about “my agent is just me.” It can simply say “stop,” then treat anything after that as trespass.

🖱️ Even with permission, the modern web is agent-hostile

Suppose every legal and policy question disappears overnight. The agent still has to deal with websites that were tuned for human eyes and human patience.

Seat selection (in flight or movies booking) is a clean example. A seat map is not a table with stable rows. Availability changes while you look. Prices might show up only after a click. Some details appear on hover. The “good seat” concept is visual and contextual. That is easy for a human scanning a screen, and surprisingly brittle for an agent that is doing perception plus planning plus action, step by step.

The timing problem is brutal. Agents pause to load, re-check state, recover from a missed click, or re-plan after an unexpected pop-up. That pause is enough for the page to refresh or inventory to change, and now the agent is acting on stale state. A flow that takes you minutes can turn into a flaky 10-minute loop of retries.

A lot of people think this is just “agents need better browsing.” The more accurate framing is that the interface is doing hidden work for humans. It compresses information into visuals and micro-interactions. Agents want the opposite, a stable, text-like, machine-readable list of options plus a reliable way to execute actions.

🧱 The “parallel web” idea is basically a structured commerce lane, is basically an API-style lane for shopping, sitting next to the normal human website lane.

On the normal web, an agent has to behave like a human, meaning it stares at pixels, figures out which button is real, deals with hover-only prices, popups, seat maps, and pages that change while it is thinking. That is why it ends up “screen-scraping,” meaning it is trying to understand the page by looking at the rendered screen, not by reading clean data.

In a structured lane, the website also exposes a machine-friendly interface, so the agent can ask something like “show flights for this route and date,” get back a structured list, pick 1 option, then call another action like “start checkout,” “hold seat,” “apply points,” and “pay.” This is what many call a “structured interface” that returns options and accepts actions, it is the same store and inventory, but the surface is designed for software instead of humans.

Some of the newest work is pushing “standard primitives” for agentic commerce, meaning predictable messages like “get product,” “create cart,” “request user confirmation,” and “complete payment,” see the . Payments networks are also framing this as a standards problem around intent, identity, and credentials, not a chatbot problem, see the push for .

This “parallel lane” approach does 2 practical things. It turns the UI from a moving target into a contract, and it gives platforms a way to enforce rules without guessing whether traffic is a scraper.

Google is pushing a similar idea with the Universal Commerce Protocol, which is also framed as an open standard that turns an AI conversation into a purchase flow by letting the agent use predictable steps to buy, rather than guessing UI behavior, see Google’s Universal Commerce Protocol docs and the deeper explanation here.

Payments companies care because checkout is where fraud and disputes show up. Mastercard’s framing is that agents need verified identity and safe credentials, so a merchant and a bank can tell “this was an agent acting for this user, with real consent,” see Mastercard’s agent verification and tokens and the newer rules discussion here.

So the “parallel web” idea is, stop forcing the agent to pretend it has eyes and a mouse, and instead give it a machine-friendly lane where it can do structured requests and structured actions.

So the point I am making is, better models alone do not fix agent shopping, you need a machine-readable commerce lane plus shared standards so agents can buy things reliably, without screen-scraping chaos.

💰 Platforms have real reasons to slow-roll BYO agents

A BBring-Your-Own (BYO) agent. that shops across sites is great for the user. It is not automatically great for the platform hosting the shopping.

A lot of e-commerce monetization relies on controlling the customer relationship and the journey. Ads, “featured” placement, and ranking are tuned to human behavior. Humans exhibit position bias, meaning they click what’s near the top because attention is limited. An agent does not have that bias. It can scan 10,000 options, compare across multiple sites, and ignore placement tricks completely.

First-party data is another piece. Clicks, scroll depth, what you hovered, what you almost bought, that behavioral exhaust is valuable because it feeds recommendations, pricing experiments, and ad targeting. A parallel machine interface can reduce how much of that behavior is even visible.

This is why the platform-controlled agent idea keeps popping up. The platform can offer its own “assistant” that preserves the platform’s data and monetization, while making it hard for outside agents to operate. That dynamic is described pretty directly in a retail analysis that mentions buying on other sites, even while third-party agents get treated as threats.

So the incentives are mixed. Better conversion and happier users are good. Losing control of the journey and data is bad.

🛡️ “Security” is not a fake excuse, it’s a real technical mess

Letting an agent browse and act creates new attack surfaces.

Prompt injection is a big one. A malicious page can hide instructions inside content that the agent reads, and the agent can mistakenly treat that content as higher priority than your actual goal, see a plain definition of . In a shopping flow, that can mean clicking the wrong thing, sending data to the wrong place, or confirming something you never intended.

Enforcement is the other hard part. A platform wants to block scrapers that harvest listings, bots that place fake orders, or competitors that surveil prices nonstop. A Bring-Your-Own (BYO) agent can look similar on the wire unless there’s a clean identity and permission model.

So “let any bot in” is not workable. The trick is allowing user-directed agents while still giving platforms tools to prevent abuse.

✅ A workable rulebook for BYO agents may look boring, and that’s good

The agent should use the user’s own session and credentials, meaning it is not running from some random data center with shared logins. That matters because it ties actions to a real account in the normal way a site already understands.

The agent should act only under user direction, meaning it does not roam and harvest. The simplest version is “do exactly this task,” plus a hard stop whenever money moves or Terms of Service acceptance is required.

The agent should identify itself and proves who it represents, meaning the site can tell “this is an automated tool acting for user X.” In practice, this is where verifiable agent identity and secure credential handling show up as core requirements, like the standards focus described in .

The agent does not do extra data harvesting, meaning it only collects what is needed to complete the transaction and handle post-purchase steps like confirmations and returns.

Once those constraints exist, a platform can still rate-limit, require extra authentication, or block abusive behavior. The difference is that the default posture stops being “all automation is banned,” and starts being “automation is allowed when it is attributable, limited, and permissioned.”

That’s a wrap for today, see you all tomorrow.

Hey, great read as always. The multi-codebook tokenizer for Qwen3-TTS speed is so smart for real-time, it reminds me of the agent challenges you rote about. Do you think this changes the game for voice-enabled agents?

The evolution of user agent capabilities in voice synthesis systems like Qwen3-TTS raises interesting questions about how these AI systems identify themselves when making requests or processing data. As TTS models become more sophisticated and autonomous, establishing clear user agent protocols becomes crucial for tracking model interactions, ensuring proper attribution, and maintaining security boundaries in distributed AI environments. The multilingual support across 10 languages also highlights the need for user agent strings that can properly convey language processing capabilities to downstream systems.