🔴 Anthropic is clamping down on unapproved Claude use by outside apps and rival platforms

Anthropic tightens Claude access, Stanford says LLMs just need coordination for AGI, and AI data centers may not justify trillion-dollar spend by 2030.

Read time: 9 min

📚 Browse past editions here.

( I publish this newletter daily. Noise-free, actionable, applied-AI developments only).

⚡In today’s Edition (10-Jan-2026):

🔴 Anthropic is clamping down on unapproved Claude use by outside apps and rival platforms.

🧱 New Stanford paper argues that LLMs already provide the raw skills for AGI, but they still need a coordination layer on top.

⏳ OPINION: AI Data Centers Have a Payback Problem, The $2T Math by 2030

🔴 Anthropic is clamping down on unapproved Claude use by outside apps and rival platforms.

So Anthropic changed its server-side checks to stop third-party tools from pretending to be the official Claude Code client while using normal Claude subscriptions.

Some coding agents were logging in with OAuth on a person’s Pro or Max plan, then sending headers that made Anthropic’s servers treat the traffic like Claude Code.

That let automated workflows run harder than Anthropic intended for a flat-rate chat subscription, which can also look like abuse when it runs in tight loops.

Anthropic’s automated abuse filters then banned some accounts because the traffic pattern looked suspicious, even when users did not realize the tool was breaking the rules.

Anthropic tightened the safeguards so spoofed “Claude Code” traffic gets blocked, and it says it is reversing bans that were caused by this specific mistake.

The technical reason they give is support and debugging, because Claude Code sends telemetry, meaning extra diagnostic signals, and most third-party harnesses do not.

Without that telemetry, Anthropic says it cannot reliably explain rate limits, errors, or bans, and users end up blaming the model for issues caused by the wrapper.

The business reason in the background is that chat subscriptions are priced for human use, while always-on agents can consume token volume that fits metered API pricing better.

🧱 New Stanford paper argues that LLMs already provide the raw skills for AGI, but they still need a coordination layer on top.

The Missing Layer of AGI: From Pattern Alchemy to Coordination Physics.

Here the LLM is a fast pattern store, while a slower controller should choose which patterns to use, enforce constraints, and keep track of state. To describe this, the author defines an anchoring strength score that grows when evidence clearly supports an answer, stays stable under small prompt changes, and avoids bloated, noisy context.

When anchoring is weak the model mostly parrots generic patterns and hallucinates, but past a threshold it switches into more reliable, goal directed reasoning, as small arithmetic and concept learning tests show. MACI then runs several LLM agents in debate, tunes how stubborn they are from anchoring feedback, inserts a judge to block weak arguments, and uses memory to track and revise decisions on longer tasks. The main claim is that most LLM failures come from missing anchoring, oversight, and memory instead of a bad pattern substrate, so progress should focus on building this coordination layer rather than discarding LLMs.

Unbaited casting represents an LLM prompted without semantic anchors, it retrieves the maximum likelihood prior, generic tokens dominated by training data. You catch common fish, not the rare target.

Left: without anchors, the model falls back to default training patterns. Like fishing without bait, you haul up lots of ordinary fish, not the specific fish you want.

Right: clear goals or context work as bait. They focus the model on the desired idea, raising the odds of retrieving the rare, relevant answer. The point is that coordination, through goals, retrieval, or constraints, shifts behavior from generic output to the target, using little extra context.

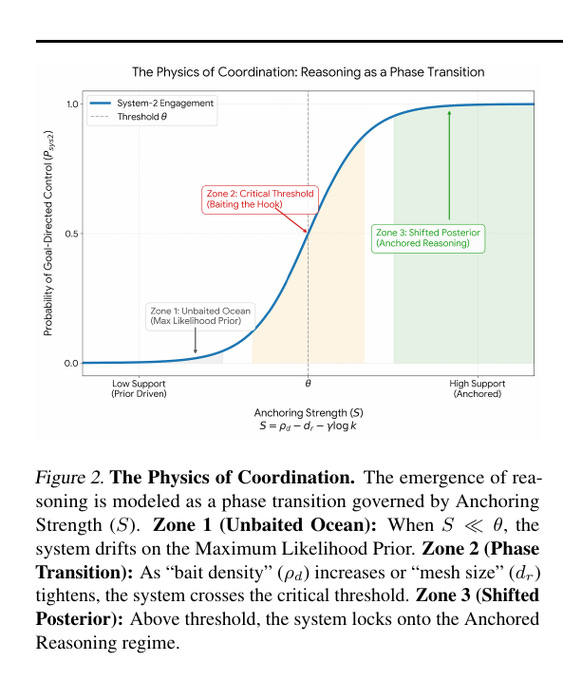

The chart says reasoning switches on when anchoring strength grows. With weak support, outputs follow training defaults, so the chance of goal directed control is near 0, zone 1.

Add clear goals, constraints, or facts, and anchoring rises. Once it passes a critical level, zone 2, behavior flips quickly, then plateaus in anchored reasoning, zone 3. Small boosts near the threshold can shift results from generic to targeted, so prompts and retrieval should push anchoring above that level.

⏳ OPINION: AI Data Centers Have a Payback Problem, The $2T Math by 2030

The aggregate capital expenditures for major U.S.-based AI hyperscalers (e.g., Amazon, Microsoft, Alphabet/Google, Meta, and others) upto 2030 is around $2Tn.

💸 Now Capex lets the spend hide in plain sight

But the capex does not hit the income statement all at once. It gets spread out over time as depreciation, meaning the accounting pain shows up slowly even if the cash left the building immediately.

That setup makes it easy to keep a straight face during the spending phase. You can have “strong earnings” while cash is being shoveled into concrete, power systems, and racks. So the real question is not “did they build it”, the question is “what cash comes back out, and how fast.”

Recent filings make the scale hard to ignore. In 1 quarter alone, the combined capex across Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta hit $112.5B, up 77% year over year.

⚡ Inference is the meter that keeps running

Training is the big upfront hit, but inference is what turns the lights into a monthly bill. This is why “AI revenue” without “AI cost of revenue” is close to useless. If a company sells an AI feature for $X, but it costs close to $X to serve at scale, that is not a product win, that is a treadmill.

Some recent reporting based on internal docs tried to put real numbers on this. It suggested OpenAI’s inference spending might have been roughly $3.8B in 2024 and roughly $8.65B in the 1st 9 months of 2025. You do not need to love the exact figures to get the point: serving frontier models at huge usage can burn cash fast.

🧾 The revenue reporting is weird on purpose

If AI was already printing money at scale, you would see clean breakouts. You would see a consistent segment line, quarter after quarter, with gross margin and growth. Instead, the industry mostly gives vibes, run rates, and cherry picked anecdotes.

Annual recurring revenue (ARR) is a good example of how this gets slippery. ARR is not the same thing as “this much revenue landed in the last 12 months.” ARR is a run rate estimate, usually “what the current pace would be if it stayed steady.” Run rate numbers can be real, but they are not profit, and they can fade if churn shows up or pricing changes.

🧩 Copilot is a good adoption test, and it looks messy

Microsoft 365 is about as close as you get to a built-in distribution machine for workplace software. So if a paid AI add-on is truly sticky and obviously valuable, you would expect it to spread cleanly there.

Instead, a lot of the public signal has been awkward. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission took Microsoft to court over allegedly misleading 2.7M customers about Microsoft 365 plans after Copilot was integrated, including claims that the cheaper “Classic” plan was effectively hidden behind the cancellation flow. The regulator also laid out that the annual Personal plan price rose 45%, from $109 to $159, after Copilot integration.

That matters here for a simple reason: if the best distribution channel still ends up relying on confusing downgrade paths and pricing bundles, demand is not as effortless as the capex curve suggests.

📦 Big contracts look like revenue, but they are not cash yet

This is where the accounting gets sneaky in a legal way. A giant contract can look like momentum, and it can even show up as backlog style metrics, but it is not the same thing as cash in the bank today.

Remaining performance obligations (RPO) is the main concept. RPO is basically “signed contracts for future delivery that have not been recognized as revenue yet.” It is a legit metric. But it is also easy to misunderstand because it is not the same thing as collected cash, and it can stretch far into the future.

A real example is the updated Microsoft and OpenAI arrangement, where OpenAI has contracted to purchase an incremental $250B of Azure services. That is massive. But it is still a commitment over time, not a guarantee that Azure will produce great margin on that spend, and not proof that end customers will pay enough for the workloads to make everyone happy.

And if you look at the supply chain, NVIDIA has talked about having $500B in bookings for advanced chips. Bookings are orders. They show demand for hardware. They do not automatically prove that the buyers are earning attractive margins after power, staffing, depreciation, and platform costs.

This is why “the winners are the chip sellers” keeps coming up. The hardware revenue is clean. The software profit pool is still getting argued about.

🧠 Why the number keeps landing around $2T by 2030

The fastest way to understand the $2T claim is to stop thinking like a product person and start thinking like a payback schedule.

If the industry spends roughly $700B to $800B across a short window on data centers and GPUs, you are not trying to earn back only that capex. You are also paying ongoing operating costs, and you are dealing with hardware that ages out faster than normal enterprise gear. So the revenue you need is not “capex divided by 5.” You need enough gross profit to cover capex refresh cycles, power, and staffing, and still leave something that looks like a normal return for the risk and scale.

Here’s the simple mental model. If your AI offerings end up with thin margins because inference is expensive, then you need gigantic revenue to justify gigantic capex. If your AI offerings end up with fat margins, then the revenue target drops a lot. The problem is that the public reporting usually talks about revenue, not margin, and the cost side is where the story lives.

So $2T is basically a proxy for “the profit pool has to get enormous,” because the cost base has already been set on fire.

💰 The Margin from AI investments varies widely

Reuters Breakingviews reported that in the 1st half of 2025 OpenAI did about $4.3B of revenue, and it cost about $2.5B to deliver, which works out to roughly 42% gross margin.

Oracle had a report based on internal documents that said it made roughly $900M renting Nvidia GPU servers, and only about $125M of gross profit, which is about 14% gross margin on that specific GPU rental business. That is brutally low compared to classic software margins, and it screams “electricity, chips, and depreciation are eating the pie.”

Then Oracle came out and tried to frame expectations, saying it expects 30% to 40% adjusted gross margins for delivering AI cloud computing infrastructure (and 65% to 80% for more conventional cloud software and business infrastructure). That’s basically Oracle saying, “yes it’s lower margin, but we think it stabilizes at a decent level once it scales.”

Google Cloud gives you an even cleaner segment read. Alphabet’s Q3 2025 filing shows Google Cloud revenue of $15.157B and operating income of $3.594B, which is about 23.7% operating margin for the Cloud segment. That includes everything Cloud sells, including AI infrastructure and AI solutions, not a pure “Gemini margin,” but it’s still one of the better public signals for whether AI workloads are helping or hurting the Cloud business.

Microsoft is the most “careful” in how it says it. In its FY26 Q1 materials, Microsoft said Microsoft Cloud gross margin % decreased to 68%, and directly blamed scaling AI infrastructure and growing usage of AI product features (partially offset by efficiency gains). That’s a real hint that AI usage is margin dilutive at the moment, at least on the reported blended gross margin line.

⏳ The constraint nobody can code their way out of, hardware ages fast

Data center builds do not last forever, but they last long enough that mistakes get painful. Dario Amoedi brilliantly explained this great “cone of uncertainty” for AI investments. Chips and data centers take ~2 years to build. But he has to decide and pay for that future compute now. But the usage of that will show up many years later.

GPUs are worse, because the performance per watt curve keeps moving. When a new generation shows up, the older chips are not useless, but they are less competitive at the exact thing that drives cost, tokens per second per watt.

That creates a weird timer. You spend huge, then you have a limited window where that hardware is “good enough” before you feel pressure to refresh. If the revenue ramp is slower than the refresh cycle, you end up stacking new capex on top of old capex without ever getting a clean payback moment.

And that is the core tension. The spending curve is clear. The cash costs of running AI are easy to describe. The revenue and margin story is still the part that keeps getting hand-waved, while the bills stay very real.

That’s a wrap for today, see you all tomorrow.