⚡ Meta open-sourced Perception Encoder Audiovisual (PE-AV)

Meta open-sources PE-AV, Nvidia grabs Groq's inference IP in a $20B move, and 2025 shifts AI focus from iteration to acceleration.

Read time: 10 min

📚 Browse past editions here.

( I publish this newletter daily. Noise-free, actionable, applied-AI developments only).

⚡In today’s Edition (25-Dec-2025):

⚡ Meta open-sourced Perception Encoder Audiovisual (PE-AV)

💰 Nvidia is taking a non-exclusive license to Groq’s AI inference tech and hiring key Groq leaders in a $20b deal while Groq keeps operating independently.

📡 The AI story of 2025 is acceleration, not iteration.

🛠️ Jensen Huang told a Cambridge Union - “Intelligence is about to be a commodity”

Meta open-sourced Perception Encoder Audiovisual (PE-AV)

so the same backbone can do cross-modal search in any direction with just dot products. Older audio-text or video-text encoders often align only 2 modalities well, so cross-modal queries like “find the video for this sound” can be brittle or domain-limited.

PE-AV extends Meta’s Perception Encoder (PE) stack with explicit audio, video, and fused audio-video towers, plus text projections that are specialized for different query pairings. On the audio side it uses a DAC-VAE (discrete audio codec variational autoencoder) to turn waveforms into tokens at about 40ms steps, then learns fusion features that can be matched with dot products against audio, video, or text embeddings.

To get captions at scale, the paper describes a 2-stage pipeline where an LLM merges weak audio captioners and video captioners into 3 caption types, then a Perception Language Model (PLM) style decoder helps refine them for tighter audio-visual correspondence. Empirically, it shows up as large jumps on broad benchmarks like AudioCaps R@1 35.4 to 45.8 and VGGSound accuracy 36.0 to 47.1, plus smaller but real gains on video like Kinetics-400 76.9 to 78.9.

💰 Nvidia is taking a non-exclusive license to Groq’s AI inference tech and hiring key Groq leaders in a $20b deal while Groq keeps operating independently.

The core hardware idea is Groq’s LPU, ts custom inference chip, basically Groq’s alternative to an Nvidia GPU for running trained LLMs. And Groq says it is deterministic, means the chip runs the model with a fixed, planned schedule, so the order and timing of operations are predictable instead of being affected by dynamic scheduling, caches, and contention that can make latency jittery on general-purpose hardware.

That predictability helps low latency because each token step can be executed with fewer surprises, so response time stays tight and consistent, which matters for real-time chat and streaming outputs. Groq also claims up to 10x less power than graphics cards.

Another lever is memory, because Groq leans on on-chip SRAM (static random-access memory) instead of relying on off-chip HBM like many GPU systems, which can speed responses but can limit the largest models that fit. SRAM and HBM are 2 different ways to feed data to the chip, and inference is often bottlenecked by “how fast can the chip read the model weights.”

SRAM (static random-access memory) is very fast memory that can sit on the chip, so the chip can grab data with very low delay and usually lower energy per access. HBM (high-bandwidth memory) is also very fast, but it sits off the chip in stacked memory packages next to the GPU, so accesses still travel farther and the system has more moving parts.

If Groq can keep more of what it needs in on-chip SRAM, it can reduce “waiting on memory,” which helps latency and sometimes power for inference. The tradeoff is capacity, because on-chip SRAM is tiny compared to HBM, so if the model’s active weights do not fit, the system has to stream from slower memory or split work across chips, which can hurt speed and cost.

Groq also describes a cluster interconnect called RealScale that tries to keep many servers in sync by compensating for clock drift. What this means is that, each chip runs on a clock, like a metronome that tells circuits when to do the next step. When you connect lots of servers together for inference, you want their “metronomes” to stay aligned so data arrives when the next chip expects it.

Real clocks are slightly imperfect, so over time one server’s clock can run a tiny bit faster or slower than another, that is clock drift. Even tiny drift can force extra buffering, retries, or waiting, which adds latency and lowers overall throughput when you are trying to run one big model across many chips.

Groq’s “RealScale” claim is basically, their interconnect plus control logic measures these timing mismatches and adjusts coordination so the cluster behaves more like one synchronized machine. So the point is not higher raw bandwidth by itself, it is keeping multi-server inference predictable and low-latency when you scale out. If Nvidia can fold these ideas into its AI factory stack, it gets another path to serve real-time inference workloads alongside GPUs.

Deep Dive: Opinion and Analysis what this really means

So the real question here is not just “did they buy it or not?” It is whether the deal basically acts like a normal acquisition, meaning control, exclusivity, and roadmap lock-in, or whether it is more like a clean, arms-length business deal, meaning narrow scope, light integration, and both sides still competing where it matters.

Groq’s funding and valuation timeline matters because it tells you what incentives are on the table and how credible the whole story is. Back in 2018, TechCrunch said Groq raised $52.3 million out of a $60 million round, based on an SEC filing, and listed Social Capital’s Chamath Palihapitiya as a participant.

Then in 2021, Groq said it closed a $300 million Series C co-led by Tiger Global and D1 Capital. Reuters later reported Groq was valued at $1.1 billion in 2021 after that Tiger Global and D1 funding. In 2024, Reuters reported Groq raised $640 million in a Series D led by Cisco Investments, Samsung Catalyst Fund, and BlackRock Private Equity Partners (plus others) at a $2.8 billion valuation. Groq said that money would go toward scaling its tokens-as-a-service business and expanding GroqCloud, and it also said it planned to deploy more than 108,000 LPUs made by GlobalFoundries by the end of Q1 2025.

Then in 2025, Reuters reported Groq raised $750 million at a $6.9 billion post-money valuation, led by Disruptive, and Groq said Disruptive put in nearly $350 million. TechCrunch also reported the same $750 million raise at $6.9 billion, and added that PitchBook estimated Groq’s total funding at over $3 billion.

The way the valuation moved lines up with a market that was mostly valuing Groq for its strategic option value in inference acceleration, not for steady, mature cash flow.

Going from $1.1 billion in 2021 to $2.8 billion in 2024 works out to roughly a 2.5x multiple, or about 155% uplift. Then jumping again from $2.8 billion in 2024 to $6.9 billion in 2025 is another 2.5x, or roughly 146% uplift. That rhythm fits a capital-heavy scaling story, not a software-style efficient scaling story, especially since Groq has been talking a lot about growing tokens-as-a-service capacity and building out more data center infrastructure.

So what’s the future

What happens next mostly comes down to whether Nvidia turns Groq-style architectural ideas into real, scaled products. Reuters said Groq avoids external High Bandwidth Memory by leaning on on-chip Static Random Access Memory, and that hints at something specific: if these inference designs work well, they could sometimes lower how much High Bandwidth Memory you need per unit of inference throughput in certain low-latency setups. That could loosen, at least a bit, the tight link between inference growth and High Bandwidth Memory supply constraints.

But the near-term infrastructure effect likely runs the other way. Making inference faster and cheaper usually grows total inference usage, which can drive more overall data center build-out even if the memory mix per accelerator changes.

So even if this stays “just” a license, it can still fit a world where networking, power delivery, and cooling keep growing because total compute deployment keeps growing, while the accelerator bill of materials shifts in niches that care more about deterministic, Static Random Access Memory-heavy inference than about fitting the biggest possible model on a single device.

Public info points to a real strategic partnership and meaningful talent transfer that helps Nvidia’s inference position and could also blunt a differentiated architectural rival. The idea that someone intentionally planted an acquisition rumor is still not backed by evidence, so it should be handled as a hypothesis, not treated like a conclusion.

📡 The AI story of 2025 is acceleration, not iteration.

Just 1 year earlier, Gemini 1.5 was still around, multimodal models struggled, DeepSeek hadn’t landed, and OpenAI’s o1 was only an early step toward agentic thinking.

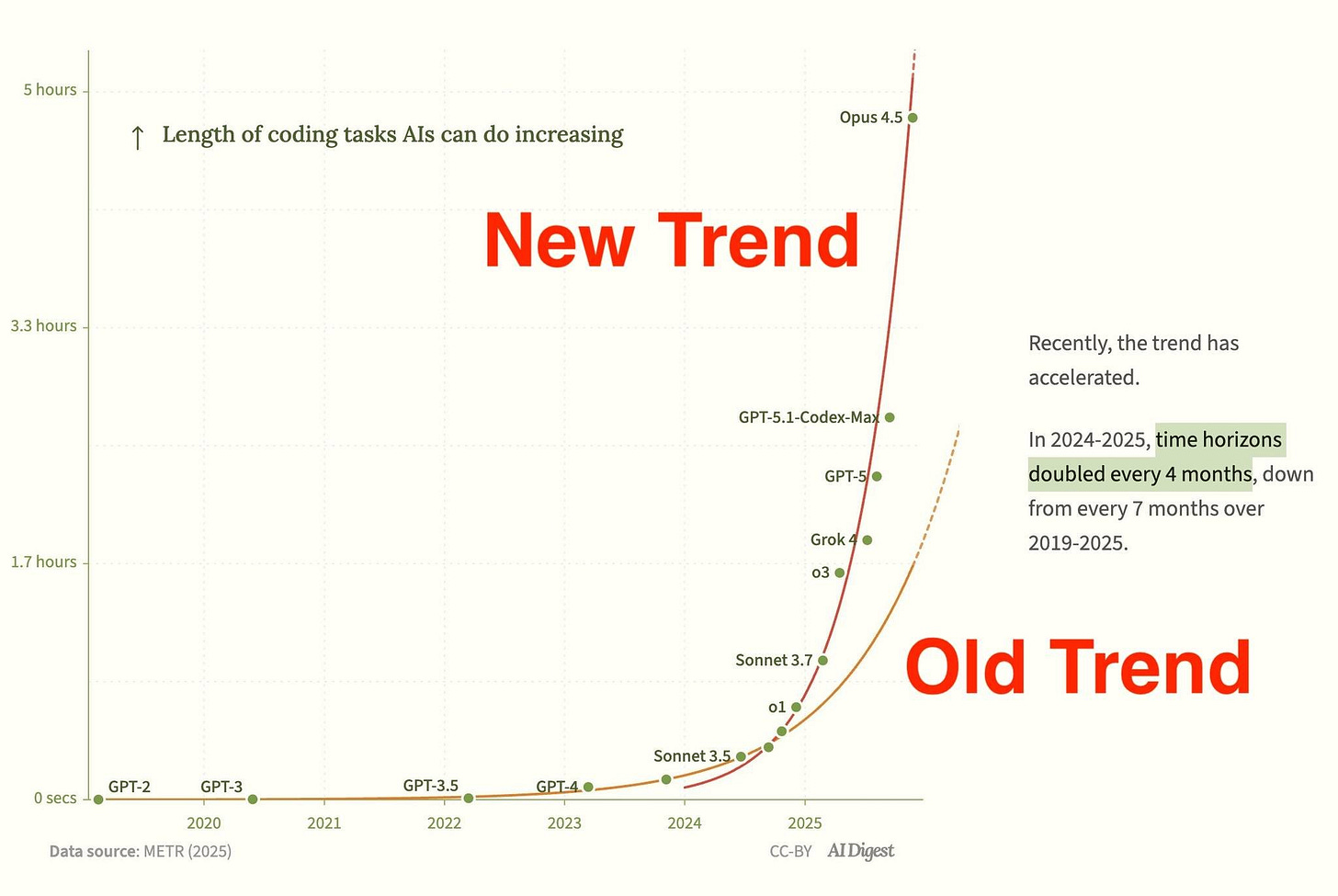

“how long an AI can keep doing a coding task without falling apart” is starting to grow way faster than it used to. For years it was basically flat, then it started climbing, and now it looks like it is bending upward hard.

Then 2025 hit. Multimodal understanding became dependable. Agent-style models started acting independently at scale.

Open-source models leveled the field. Work that once took engineers months dropped to hours or minutes. Researchers found task length capability doubling every 7 months, which made each new model feel like a massive leap.

Looking ahead to 2026, if the trend holds, AI won’t just assist workflows, it’ll run them, and today’s wins will feel small fast.

If you are building with this, the practical insight is that the bottleneck shifts. When models only handle short tasks, your biggest problem is prompt quality and code correctness on a small diff. When models handle multi-hour coding arcs, your biggest problem becomes planning, state management, and trust. You need better ways for the AI to keep an internal map of the repo, remember decisions it made earlier, and prove what it changed.

🛠️ Jensen Huang told a Cambridge Union - “Intelligence is about to be a commodity”

For a long time, school and hiring treated “smart” as scarce, because fast recall and clean problem solving were hard to scale beyond the best individuals.

AI has flipped that. Read the full blog.

Jensen explained “When AI takes over all standardized work, the only value humans have left is to handle the poorly defined work.”

“The poorly defined work is the most valuable of all work.”

- Defined Work (AI Territory)

- Poorly Defined Work (Human Territory)

That’s a wrap for today, see you all tomorrow.

Brilliant insights! Acceleration, not iteration, is so true.