ML Interview Q Series: Is increased revenue but decreased user searches after adding more ads a positive or negative outcome?

📚 Browse the full ML Interview series here.

Comprehensive Explanation

When a search engine company decides to include additional ads for certain queries, it must carefully balance the monetization gains versus the impact on user experience and user retention. Observing a rise in total revenue indicates that, in the short term, monetization strategies are paying off. However, a decline in overall query volume suggests there may be some negative effects on user engagement or user satisfaction. If users are discouraged by too many ads, they may reduce their usage of the platform or switch to a competitor’s service for future searches.

The key insights hinge on understanding user behavior and the long-term value of each user. Short-term spikes in ad revenue could be offset by users abandoning or reducing usage of the platform if they find the user experience diminished. This also has implications for how a search engine ranks its organic results, as more ads can push down organic listings and make it less convenient for users to find desired information.

Measuring the net gain or loss over time requires more fine-grained data analysis. One approach is to examine any shifts in users’ click-through rates, session duration, and repeat visit frequency. If the user base or query volume continues to fall, it might suggest lasting damage to user trust or user experience. On the other hand, if the drop in search volume is slight and stabilizes, but the ad revenues remain sufficiently higher, the net effect might still be acceptable from a business standpoint.

Another angle is user segmentation. Perhaps some types of users are unaffected (continuing to conduct similar search volumes), while others, particularly those sensitive to ad clutter, reduce their usage. Understanding which user segments are most affected is critical to determining if the increased ads have a strategic benefit or if they risk alienating a crucial audience.

Finally, the competitive landscape matters. If another major search engine provides a less intrusive advertising model and offers users a better experience, the risk of losing users is greater. If your company is in a dominant market position, you might still retain users despite increasing ads, as long as the perceived utility remains sufficiently high.

How to Evaluate the Trade-Off Quantitatively

One detailed way to interpret this scenario is to analyze lifetime value (LTV) of a user. Suppose we define total revenue from a given user over an extended period as a function of how many searches they conduct, how often they click ads, and the cost per click the advertiser pays.

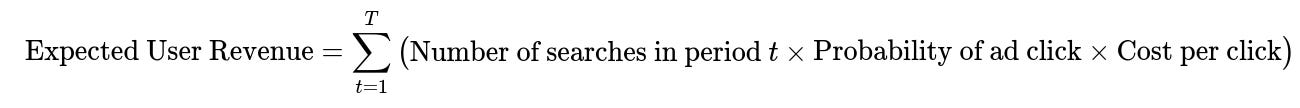

We could attempt a simplified relationship for expected user revenue:

Where:

T is the total number of time periods (days, weeks, months, or any relevant intervals).

Number of searches in period t is how many times a user searches during that interval.

Probability of ad click represents how likely the user is to click an ad per search within that period, which might vary over time.

Cost per click is the revenue that the search engine generates for each ad click.

A short-term revenue boost can be seen if cost per click remains stable while more ads are displayed and perhaps more clicks occur. However, if the Number of searches in period t drops significantly in future intervals because users decide to avoid the search engine, the net present value of that user’s lifetime revenue might be lower. Thus, balancing the short-term gains (increasing ads) with long-term retention (user loyalty and sustained query volume) is crucial.

Potential Follow-Up Questions

How would you test if the decrease in search volume is directly attributable to the increase in ads?

One straightforward approach is to use A/B testing. Segment a portion of users (treatment group) who see the increased number of ads and compare their search behavior to a control group seeing the normal number of ads. By comparing changes in search frequency, user sessions, and clicks between these two groups, you can assess whether the presence of additional ads leads to a statistically significant drop in search volume or user engagement.

Statistical analyses like significance testing (e.g., t-tests, confidence intervals) would be used to verify that observed differences are not simply due to random variation. If the treatment group shows a substantial and statistically significant drop in search activity that does not stabilize, this is a strong indicator that ads are the root cause.

Why might revenue increase initially, but then plateau or decline if the trend continues?

If adding more ads initially leads to higher click rates or better monetization from existing traffic, revenue may spike early on. However, some users could become annoyed or overwhelmed by the cluttered experience, causing them to reduce usage or switch to another platform. As this user attrition accumulates, the pool of available searches and potential clicks decreases, potentially offsetting or negating the initial revenue gains. This phenomenon can manifest in a plateau or even a long-term decline in revenue if user dissatisfaction grows.

What metrics would you recommend monitoring over time to decide if the change is acceptable?

It is critical to look at a blend of metrics that capture both financial performance and user engagement:

Total Revenue: Observing whether the higher number of ads continues to yield increased earnings in the medium to long run.

User Retention Rates: Checking how often users return to conduct future searches.

Daily/Monthly Active Users (DAU/MAU): Monitoring the overall size of the user base and whether it is stable or shrinking.

Session Length: Investigating whether users who do come to the site remain as long as before.

Search Frequency per User: Studying how many queries each user performs in a given session or time period.

Survey or Feedback Scores: Gathering qualitative data on whether users perceive the increased ads as bothersome or acceptable.

If these indicators remain healthy while revenue remains higher, it implies the shift in ad policy can be sustained with minimal negative impact. If key usage metrics show a steady downward trend, it might be a warning that user dissatisfaction is on the rise.

How do you balance user experience vs. revenue in such decisions?

It often comes down to product strategy and the organization’s long-term vision. Some companies adopt a user-first philosophy, meaning that preserving user trust and ensuring a streamlined search experience takes priority, even if it means sacrificing near-term revenue boosts. Others may optimize primarily for revenue, especially if they believe they have a strong market position and that user churn will be minimal. Most companies try to find a balance between these extremes, using data-driven experimentation to figure out how many ads can be placed before a noticeable drop in user satisfaction and retention occurs.

Continual feedback loops from user data, A/B testing, and competitive analysis enable search engine companies to gauge the acceptable threshold of ads. This process ensures that while monetization strategies are advanced, user experience does not suffer to a point where the platform’s long-term health is jeopardized.

Below are additional follow-up questions

How might external factors (such as seasonality or competing platforms) affect the observed drop in searches?

A decline in query volume might coincide with natural fluctuations or trends outside of the increase in ads, such as seasonal events (holidays or end-of-year lulls) or users shifting their behavior to different platforms. For instance, if competitor platforms have significantly improved their search and ad experiences, some users could migrate there irrespective of changes in your platform’s ad load. A rigorous way to test this is to incorporate baseline models of user behavior that account for known external factors (e.g., time-of-year, news cycles, or competitor announcements). By subtracting these expected seasonal or competitive effects from the actual change, you can isolate any unexplained variation that is more likely related to your own ad policy changes. In addition, market-level trends can be monitored using third-party reports or broader industry metrics to ensure that any shifts in usage are not simply a reflection of general macro-level changes (like an economic downturn that decreases internet traffic overall).

Could mobile and desktop usage trends differ in their response to increased ads?

Mobile search behavior often involves quicker sessions, smaller screen space, and possibly more sensitivity to clutter. On a smaller screen, even a modest increase in ads can take up a significant portion of the viewport, pushing organic results far below the fold. This could frustrate mobile users at a faster rate compared to desktop users, leading them to reduce their usage more dramatically. On the other hand, desktop users might tolerate or ignore additional ads more easily because of larger screen real estate. To handle this nuance, consider segmenting metrics by device type—monitor search volume, click-through rates, and bounce rates separately for mobile vs. desktop. Determine if one segment’s engagement is disproportionately affected, and design targeted strategies (e.g., fewer or differently placed ads) tailored to that segment.

How do we ensure ads are relevant to the user’s intent and not just increasing noise?

Increasing ad volume does not necessarily mean losing user trust if those ads are highly relevant to the query. The more aligned the ads are with user intent, the more likely users will find them helpful rather than intrusive. However, if ads are not contextually matched, the user may feel spammed. One best practice is to maintain or even enhance relevance signals. This might involve analyzing user click patterns, semantic matching between queries and ad content, and user feedback loops (e.g., letting users report irrelevant ads). If your machine learning ad-targeting algorithms become more refined, you could offset the negative impact of extra ads by ensuring they remain useful. Continuous monitoring of metrics like user satisfaction scores, ad click-through rate in relation to query type, and user feedback can reveal how well the system is matching ads to user needs.

What if short-term data appears inconclusive or contradictory?

Sometimes data from a short time window can be noisy, making it hard to draw firm conclusions. It is possible that immediate reactions to additional ads include novelty effects—where some users initially click out of curiosity—or random fluctuations that confound the real user response. A recommended approach is to perform longer-duration experiments (e.g., multiple weeks or months) and track cohorts over time. By observing how new and existing users behave over these extended intervals, you can distinguish transient novelty effects from sustained behavioral changes. Implementing sequential testing (periodically reviewing partial results while the experiment continues) also helps catch early warning signs of user drop-off or changes in click behavior, but final decisions often require adequate time for stable data and patterns to emerge.

Can user churn escalate once a tipping point in ad load is reached?

User tolerance to ads might be nonlinear, where a small increase causes little pushback, but crossing a certain threshold triggers accelerated churn. For instance, users might quietly endure one or two additional ads per page, but after a certain threshold, the experience could feel so cluttered that users abruptly start searching less or switch providers. Tracking user churn can be approached with survival analysis methods to identify the point in time when a user’s probability of leaving the platform spikes. This can be coupled with analyzing dwell time, repeated search frequency, and user feedback to detect that “tipping point.” By pinpointing the threshold at which dissatisfaction sharply rises, you can calibrate ad load to remain below that level or adjust how ads are displayed to minimize friction.

Could there be unforeseen impacts on organic search ranking and website ecosystem?

When a search engine includes more ads, organic results get pushed down the page. Website owners who rely heavily on organic traffic might see reduced visibility and traffic, affecting their willingness to cooperate with the search engine in other ways. This could mean fewer websites optimizing for your search engine or less adoption of your platform’s tools, possibly undermining the broader ecosystem that supports your revenue model. To assess this risk, monitor fluctuations in organic click-through rates, track feedback from content creators, and watch for changes in how often websites are optimized for your search engine vs. competitors. If organic site owners perceive the environment as unfavorable, they may optimize more vigorously for competitor platforms, impacting your long-term market share.

What strategies could be employed if we find that the higher ad load is causing unacceptable user churn?

If user churn or lowered engagement is clearly tied to the increased ads, a few remedial strategies might be undertaken:

• Dynamic Ad Throttling: Automatically decrease ad load when early signals show a user is becoming disengaged. This could be triggered by certain patterns (e.g., user quickly exits the search page or shows unusual scrolling behavior). • Relevance-Driven Placement: Ensure that only ads with strong contextual relevance are displayed, and reduce low-value or tangential ads that contribute to clutter. • Optimized Layout: Reorganize page design so ads do not overly disrupt organic listings, possibly integrating them more seamlessly. • Tiered Experimentation: Roll out ad load changes to smaller user groups first, observe changes in usage metrics, then proceed incrementally.

The effectiveness of these strategies can be measured through new experiments, closely watching user retention, time-on-page, and ad-derived revenue.