Read time: 16 min

📚 Browse past editions here.

( I publish this newletter daily. Noise-free, actionable, applied-AI developments only).

⚡Top Papers of last week (4-Jan-2026):

🗞️ Attention Is Not What You Need

🗞️ From Word to World: Can LLMs be Implicit Text-based World Models?

🗞️ mHC: Manifold-Constrained Hyper-Connections

🗞️ IQuest-Coder-V1 Technical Report.

🗞️Vibe Coding in Practice: Flow, Technical Debt, and Guidelines for Sustainable Use

🗞️ Professional Software Developers Don’t Vibe, They Control: AI Agent Use for Coding in 2025

🗞️ What Drives Success in Physical Planning with Joint-Embedding Predictive World Models?

🗞️ Recursive Language Models

🗞️ Decoupling the “What” and “Where” With Polar Coordinate Positional Embeddings

🗞️ End-to-End Test-Time Training for Long Context

🗞️ Attention Is Not What You Need

This is great. 🔥 The paper propose an attention-free sequence model built around Grassmann flows.

says a model can replace self attention with a structured “Grassmann flow” mixing layer that stays competitive while scaling linearly with sequence length. The big deal is that it directly challenges the usual assumption that good sequence models must build an all pairs attention matrix, and it shows a concrete, working alternative that never computes those attention weights.

The alternative works by first shrinking each token’s hidden state into a smaller vector, then looking at local token pairs and treating each pair as a tiny 2D subspace, which is a geometric object that can be encoded into features and mixed back into the model. It avoids the L by L attention matrix, so the expensive part does not blow up quadratically as the context gets longer, at least in the math of the method.

Self attention works by making a weight for every token pair, so each token can pull information from all the others. So the paper argues attention behaves like lifting the model into a huge pair interaction space that is hard to summarize cleanly, while the Grassmann based features live in a finite structured space that is more amenable to analysis. The evidence is not “it beats Transformers on language modeling”, it is “it gets within about 10% to 15% on WikiText 2 without any attention, and a Grassmann based classifier head slightly edges a Transformer head on SNLI”, which is enough to prove the core claim is plausible.

🗞️ From Word to World: Can LLMs be Implicit Text-based World Models?

This paper turns an LLM into a “world simulator” that predicts what happens next after an agent acts. It treats language modeling as next-state prediction in an interactive loop, then tests when this is reliable and useful for training agents.

After training on recorded chats (supervised fine tuning), their models reach about 99% next state accuracy in structured environments. The paper starts from an experience bottleneck, reinforcement learning agents improve by trying actions and seeing outcomes.

Real environments are slow to sample, so the authors test this idea in 5 text environments. Here the world model reads the history plus the next action, then predicts the next observation and a success flag.

They judge it on 3 things, fidelity and consistency, meaning correct next states over many steps, scalability with more data and bigger models, and utility for agents. A few examples in the input (prompting) help in structured games, but extra training makes long simulations much more stable.

Open ended settings like web shopping are tougher because results vary, so the simulator drifts unless tied to real observations. A good simulator lets agents test irreversible actions before doing them, generate extra practice episodes, and start learning with a better action strategy.

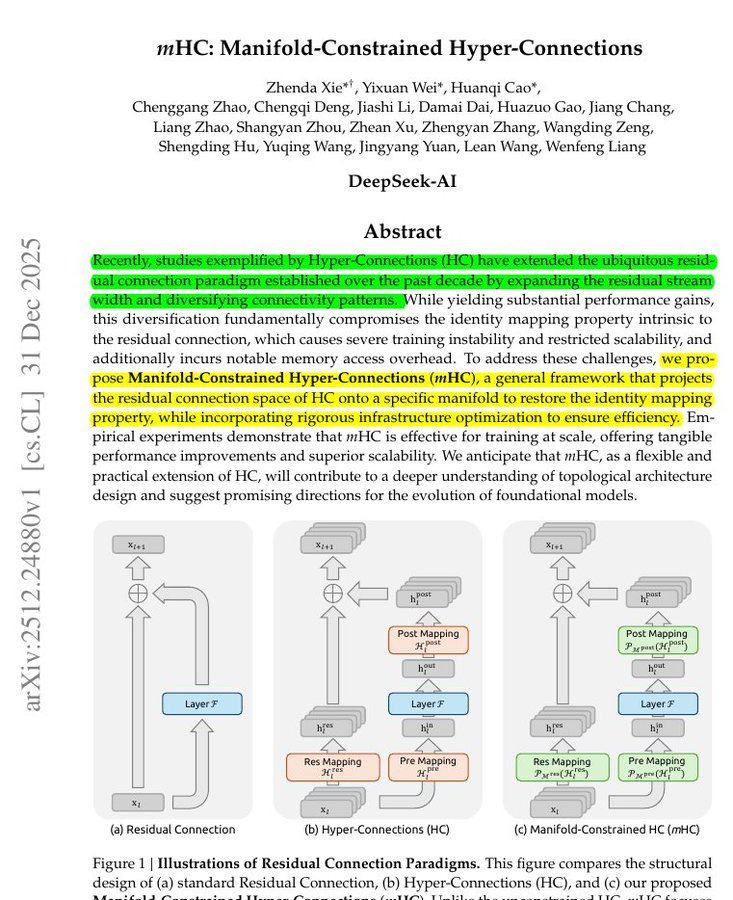

🗞️ mHC: Manifold-Constrained Hyper-Connections - The famous DeepSeek Paper

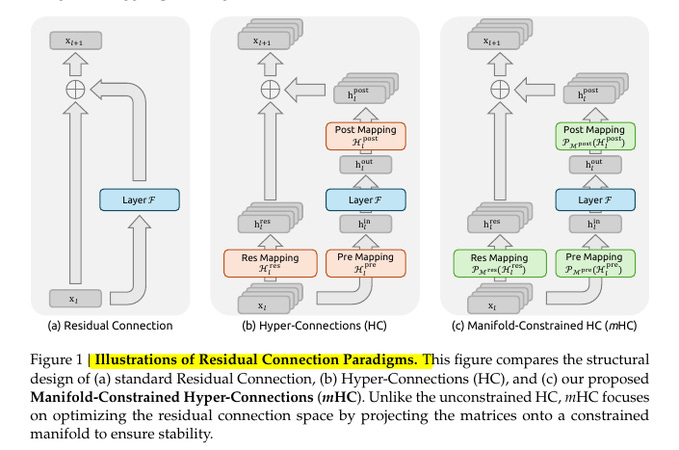

DeepSeek dropped a core Transformer architecture improvement. A traditional transformer is basically a long stack of blocks, and each block has a “main work path” plus a “shortcut path” called the residual connection that carries the input around the block and adds it back at the end.

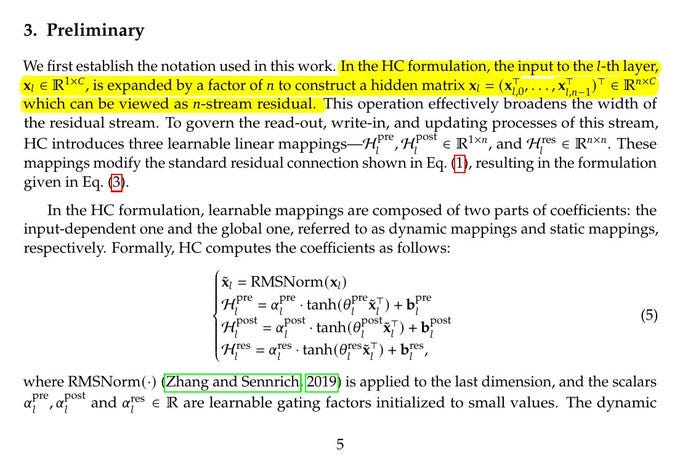

Each block in this original transformer architecture does some work (self attention or a small feed forward network), then it adds the block’s input back onto the block’s output, which is why people describe it as a “main path” plus a “shortcut path.” Hyper-Connections is a drop-in change to that shortcut path, because instead of carrying 1 stream of activations through the stack, the model carries a small bundle of parallel streams, then it learns how to mix them before a block and after a block.

Standard Transformers pass information through 1 residual stream. Hyper-Connections turn that into n parallel streams, like n lanes on a highway. Small learned matrices decide how much of each lane should mix into the others at every layer.

In a normal residual connection, each layer takes the current hidden state, runs a transformation, then adds the original back, so information can flow forward without getting stuck. In this new Hyper-Connections, the layer does not see just 1 hidden state, it sees a small bundle of them, and before the layer it learns how to mix that bundle into the input it will process.

So in a traditional transformer block, wherever you normally do “output equals input plus block(input),” Hyper-Connections turns that into “output bundle equals a learned mix of the input bundle plus the block applied to a learned mix,” so the shortcut becomes more flexible than a plain add. After this learned layer, the “Hyper-Connections” mechanism again learns how to mix the transformed result back into the bundle, so different lanes can carry different kinds of information, and the model can route signal through the shortcut in a more flexible way.

The catch is that if those learned mixing weights are unconstrained, stacking many blocks can make signals gradually blow up or fade out, and training becomes unstable in big models. This paper proposes mHC, which keeps Hyper-Connections but forces every mixing step to behave like a safe averaging operation, so the shortcut stays stable while the transformer still gets the extra flexibility from multiple lanes.

The paper shows this stays stable at 27B scale and beats both a baseline and unconstrained Hyper-Connections on common benchmarks. HC can hit about 3000x residual amplification, mHC keeps it around 1.6x.

This image compares 3 ways to build the shortcut path that carries information around a layer in a transformer.

The left panel is the normal residual connection, where the model adds the layer output back to the original input so training stays steady as depth grows. The middle panel is Hyper-Connections, where the model keeps several parallel shortcut streams and learns how to mix them before the layer, around the layer, and after the layer, which can help quality but can also make the shortcut accidentally amplify or shrink signals when many layers stack. The right panel is mHC, which keeps the same Hyper-Connections idea but forces those mixing steps to stay in a constrained safe shape every time, so the shortcut behaves like a controlled blend and stays stable at large scale.

What “hyper-connection” means here.

You widen the residual from size C to n×C, treat it as n streams, and learn 3 tiny mixing pieces per layer. One mixes the residual streams with each other, this is the crucial one. One gathers from the streams into the layer. One writes results back to the streams. The paper’s contribution is to keep the first one in the safe “doubly stochastic” set, so it mixes without amplifying.

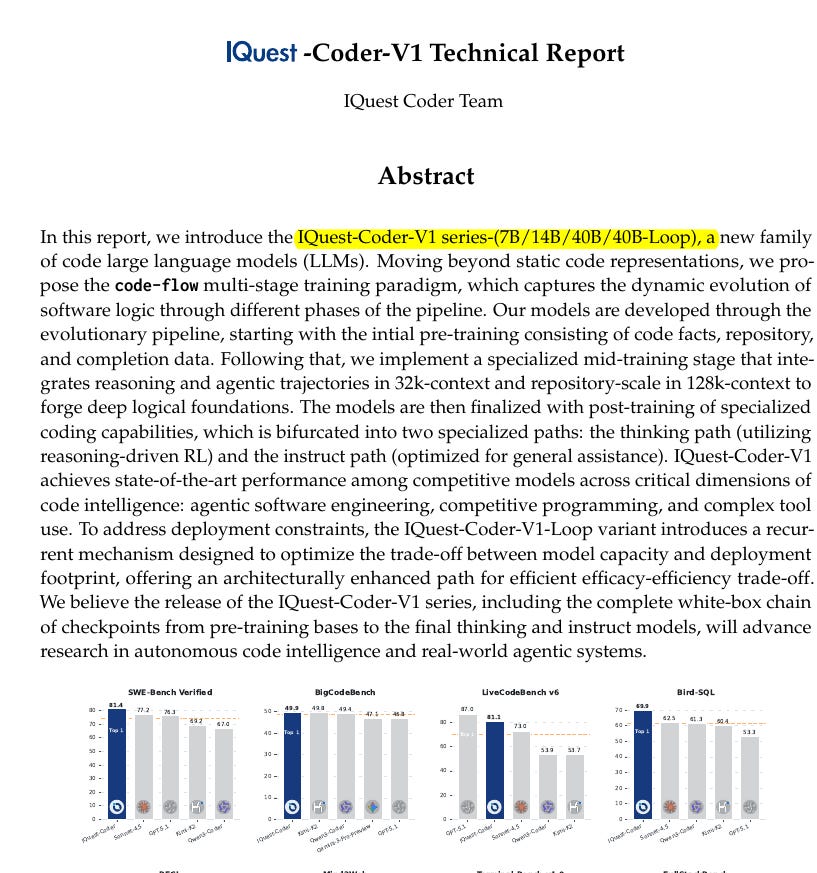

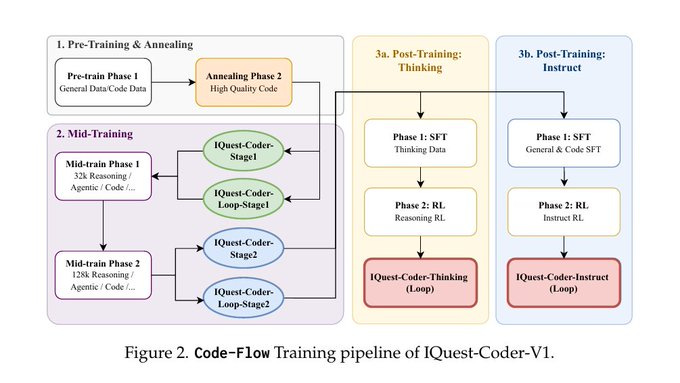

🗞️ IQuest-Coder-V1 Technical Report.

China’s new opensource code model IQuest-Coder beats Claude Sonnet 4.5 & GPT 5.1 despite way fewer params.

SWE-Bench Verified (81.4%), BigCodeBench (49.9%), LiveCodeBench v6 (81.1%) - with just 40B-param model.

The big data idea is code flow, training on repository commit transitions, so the model learns how patches evolve a codebase. LoopCoder also changes the usual transformer setup, by running the same layer stack 2 times with shared weights.

A normal transformer has a long chain of layers, and each layer has its own separate weights, so the model does 1 forward pass and whatever it wrote early tends to “lock in” as it keeps going. LoopCoder instead reuses the same layer stack 2 times, so it is like giving the model a 2nd chance to process the exact same context with the exact same “brain,” but after the 1st pass has already formed an internal draft of what matters.

The shared weights part matters because the 2 passes behave like an iterative refine loop rather than 2 different models stacked, so the 2nd pass naturally learns “fix and tighten what I just thought,” instead of learning a totally new transformation. Attention is how the model chooses what earlier text to focus on, and LoopCoder mixes global attention over the 1st pass with local attention over the 2nd pass, then uses a learned gate to blend them.

This helps on real coding tasks because repo bugs are rarely solved by a single clean completion, you usually need 1 pass to spot the likely file, function, and failure mode, then another pass to apply a careful edit that matches surrounding code and avoids breaking other parts. Before final tuning, they mid train with 32K and 128K token contexts (a token is a short text chunk) on reasoning and agent trajectories that include tool commands, logs, errors, and test results.

full training recipe for IQuest-Coder-V1

It starts with normal pre-training on mixed general text and code, then an extra annealing step on higher quality code, which is basically a cleanup and sharpening pass before the harder training begins. The mid-training block is the big shift, because they push long context (32K then 128K tokens) and feed the model reasoning traces plus agent style trajectories, meaning sequences that look like “try something, see tool output or errors, then adjust.”

🗞️Vibe Coding in Practice: Flow, Technical Debt, and Guidelines for Sustainable Use

This paper says vibe coding speeds a quick first product demo, but it piles up tech debt that bites later. This is one of the first papers to clearly name and explain the flow versus debt tradeoff, where AI driven coding boosts short term speed but systematically creates hidden problems in security, architecture, testing, and maintenance.

In 7 vibe-coded prototype apps, 970 security issues showed up, and 801 were tagged high severity. Vibe coding means a developer describes the feature in plain English, and a generative AI model generates most of the code for a Minimum Viable Product, the smallest version that still works.

That fast loop feels smooth because new screens and features appear in minutes, but tech debt builds up, meaning later changes get slow and risky. The authors trace the debt to vague prompts, missing non-functional requirements like security and speed, and repeated regenerations that quietly change earlier design decisions.

One real example was a bug that stayed unfixed while the AI rewrote how data moved around, added new server routes, and grew the codebase by 100s of lines. Their main advice is to treat AI output as a first draft, then add guardrails like structured prompts, clear module boundaries, prompt and version logs, real tests, and automated security checks.

🗞️ Professional Software Developers Don’t Vibe, They Control: AI Agent Use for Coding in 2025

This paper shows that professional developers use coding agents, but stay in tight control. From 13 observed sessions and 99 survey responses, the authors find that professionals do not vibe code.

In Vibe coding, the developer trusts the agent so much that they stop reviewing changes carefully. Experienced developers instead plan the work themselves, then give the agent very specific instructions, context, and limits.

They make the agent work in small chunks, then they verify by running tests, running the app, and reviewing the changes. They report agents help most with straightforward chores like writing starter code, writing tests, updating documentation, simple refactors, and small bug fixes.

They report agents struggle with complex logic, deep business rules, fitting into old codebases, security-sensitive work, and big design decisions. The takeaway is that agents are treated like fast assistants, and software quality still depends on human judgment and verification.

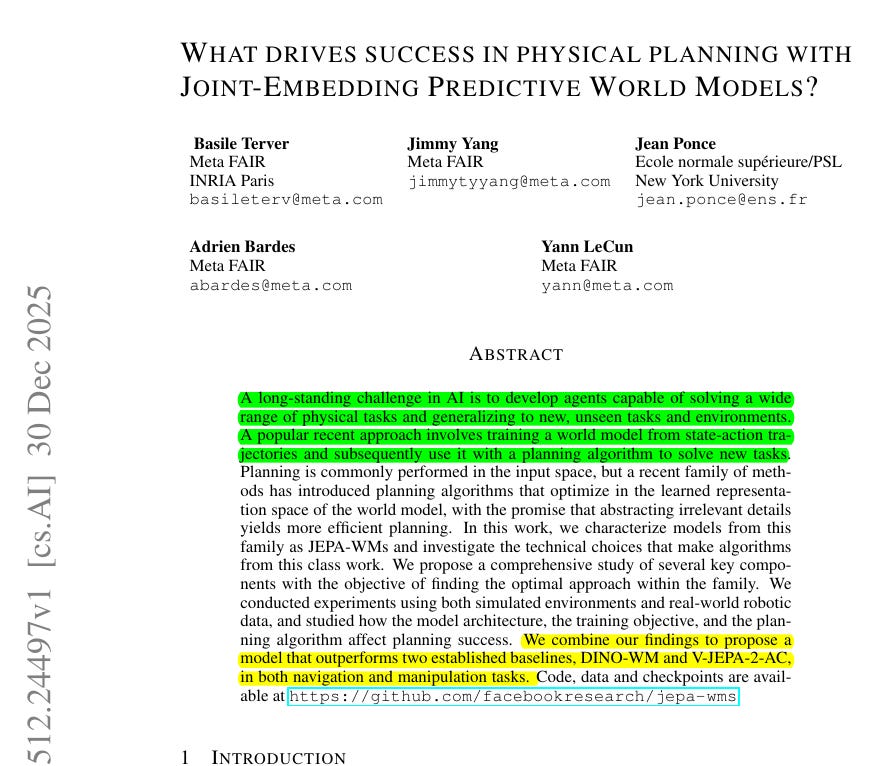

🗞️ What Drives Success in Physical Planning with Joint-Embedding Predictive World Models?

New Paper from ylecun, Meta and New York University. “What Drives Success in Physical Planning with Joint-Embedding Predictive World Models?”

Making a robot that can understand its environment and generalize to new tasks is still one of the biggest hurdles in modern AI. And to teach that, the idea starts with teaching the robot how the world behaves by watching interactions, such as how objects move when pushed. That knowledge becomes a world model the robot can use to plan.

Earlier AI planned straight from raw inputs like pixels and motor values. Newer approaches plan inside a simplified internal space that keeps important structure and ignores distractions.

These are called JEPA-WMs, short for joint-embedding predictive world models. The paper asks what design choices actually matter, and tests this through large experiments in simulation and real-world robots, looking closely at model design, learning goals, and planning methods.

The big deal that this paper achieves is that earlier JEPA world models have been a nice idea, plan with a learned predictor instead of pixels, but performance has been inconsistent because lots of small choices decide whether planning is stable or falls apart. So they isolate those choices with large controlled sweeps and show that success is mostly about making the embedding space and the planner agree, so the planner’s simple distance-to-goal objective points toward actions that really move the robot the right way.

Concretely, they find that a strong frozen visual encoder like DINO makes embeddings that keep the right physical details for planning, while some video-style encoders can blur away what the planner needs. They show planning works best with sampling-based search like Cross-Entropy Method (CEM), because it can handle discontinuities from contact, friction, and gripper events where gradient planners often get stuck.

They show the predictor must be trained to handle short unrolls, because planning feeds predictions back into the model, and pure teacher-forcing can look good on 1-step errors but drift when rolled out. They identify simple, practical constraints like needing at least 2-frame context to infer motion, and matching the planning window to what the model was trained to use.

Then they combine these into an improved JEPA-WM that beats DINO-WM and V-JEPA-2-AC across simulation and real-robot benchmarks, including navigation and manipulation. The mechanism is mostly about shaping a search-friendly cost landscape in embedding space, and the recurring weak spot is contact and gripper details that an embedding distance can miss. The practical impact is that teams can treat this as a checklist for building a planning-capable world model, instead of guessing which encoder, rollout loss, context length, and planner will work together.

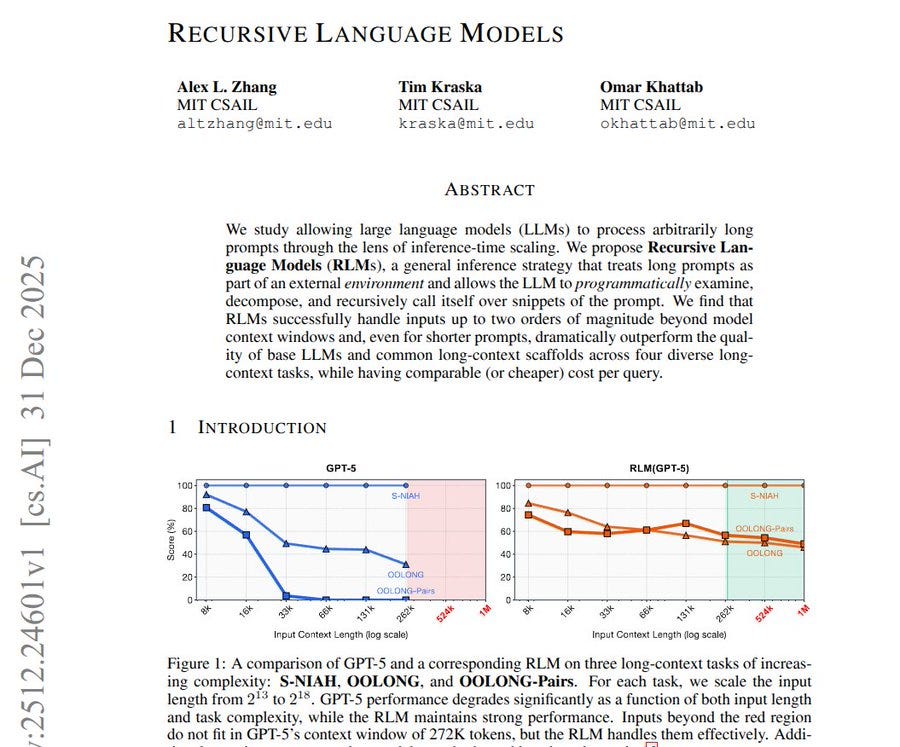

🗞️ Recursive Language Models

Normal LLMs have a hard context window, and their answers get worse as the input gets longer and more complex. This paper shows a setup where an LLM can work with inputs past 10M tokens by keeping that text outside the model’s normal context window.

The model is not truly “holding 10M tokens in context” at once, it is repeatedly fetching small pieces from a much larger external text store and then reasoning over them. The paper says language models can read very long prompts by treating the prompt as external data.

The authors store the whole prompt in a Python mini coding workspace, so the LLM can pull snippets and run extra model calls on them. Then let the model use a Read-Eval-Print Loop tool to search and pull small snippets when needed.

They tested this Recursive Language Model idea on big document research, long list reasoning, and codebase questions, and compared against summarizing or retrieving chunks. It stayed reliable even past 10M tokens, meaning small text pieces, and often beat plain LLM calls without retraining by reading only what matters.

🗞️ Decoupling the “What” and “Where” With Polar Coordinate Positional Embeddings

OpenAI co-authored this paper along with other top labs.

Introduces Polar Coordinate Position Embedding (PoPE), a new way to tag token positions without mixing location into meaning. Shows common position tagging can mix what and where, then fixes it with a cleaner position signal.

LLMs can lose track of where things are, and PoPE is a simple way to keep positions straight. On a pointer style indexing task, PoPE hits about 95% accuracy, while Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE) stays near 11%.

In a Transformer, attention is the lookup step that picks which earlier tokens to use, and RoPE is a popular position tag for it. The paper argues RoPE can blur what and where because token content can shift the position signal inside the attention score.

PoPE changes the rule so content only sets a strength value, while position only sets a turn amount, making these 2 signals easier to combine. The authors trained matched models on music, genome letter sequences, and web text, and they checked standard language tests without task specific training.

PoPE generally reduced prediction errors, and it kept working when test inputs were about 10x longer than the training length. This matters because long documents and long prompts need clean position handling to copy, count, and refer back correctly.

Why PoPE holds up on longer contexts vs RoPE ?

RoPE encodes position by rotating features, position is stored as a rotation angle inside each frequency channel.

Some channels rotate very slowly, meaning their angle changes only a tiny bit when you move 1 token, so they are the channels that can represent very long-range distances. When you compare 2 tokens that are far apart, the model relies a lot on those slow channels to tell “this is 5000 tokens away” versus “this is 5001 tokens away.”

If the angle in a slow channel is even slightly off, then at long distances the direction can end up closer to the “wrong offset” than the right one, so the attention score peaks at the wrong location.

A simple way to picture it is a clock hand that moves almost not at all each step, so if the hand is mis-set by a small amount, after many steps the reading you infer about “how many steps happened” can point to the neighboring tick instead of the correct one.

RoPE also lets token content nudge the starting angle of a feature, so the model is not only asking “how far apart are these tokens,” it is also quietly letting “what the token is” shift the distance signal.

That content-driven shift is usually tolerable at the training length, but it becomes unstable when the model is forced to compare tokens that are thousands of steps apart, because the model is leaning on the slow channels and those channels are easy to drift.

PoPE removes that failure mode by forcing position to control only the rotation angle and forcing content to live only in the feature magnitude, so long-range distance is not getting warped by token-specific content quirks.

So when the model goes from a 1024-token training window to a 10240-token test window, PoPE is still doing the same clean “relative offset” computation, instead of accidentally changing what “offset” means depending on which words happen to be in the query and key.

🗞️ End-to-End Test-Time Training for Long Context

New Nvidia and other top lab paper claims long context can come from test time learning, while keeping attention cheap and fast.

With full attention, every new token, a small chunk of text, checks all earlier ones, so cost grows with context, and short windows forget.

They keep a standard Transformer that only looks back over a recent window, then update part of its weights, the model’s stored numbers, while reading the input text by predicting the next token.

During training, they use meta learning, meaning they train the model to learn quickly from its own input text, so test time updates help instead of hurt. They test on language modeling at up to 128K context and compare against sliding window Transformers, Mamba 2, Gated DeltaNet, and earlier test time training, and they also run needle in a haystack recall checks.

For a 3B model, it keeps quality from dropping as context grows and stays constant time per token, reporting 2.7x faster input processing than full attention at 128K.

Full attention still wins when the job is exact string recall, but this work shows a practical path to long context without the attention cost exploding as context grows.

That’s a wrap for today, see you all tomorrow.

The attention is not what you need paper looks like a poorly framed and really badly implemented attempt at getting skew-symmetric 2-forms in a sliding window attention formulation.